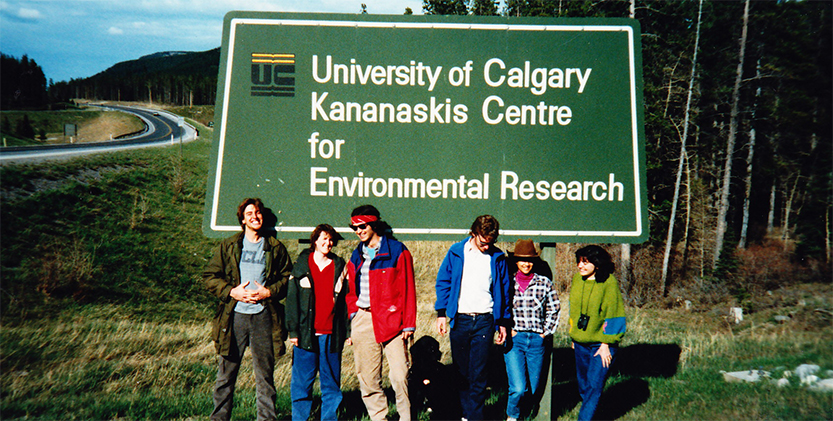

Wickett Summits in the Rockies – June 1989

It was my first year as a student at York University’s faculty of environmental studies. I had just graduated from York with a double major honors B.A. in psychology and sociology, but my thirst for knowledge wasn’t fulfilled – I wanted to pursue a Masters.

The master’s in environmental studies program allows students to be self directed, if their supervisors support the learning plan. My first year would be spent doing course work, which after two years of college and four years pursuing my B.A., was getting a bit tiring. I wanted to conduct field research. So, when the opportunity came along to spend four weeks in the Rocky Mountain foothills conducting field research with a small team, I jumped at the chance.

Our team was stationed at the Kananaskis Research Centre in western Alberta. Nearby, was a mountain our leader was familiar with, and he suggested we leave early the next morning with a plan to summit the mountain and be back that same day. Naturally, I wanted to go.

The leader took me aside and suggested that I sit this one out. He told me grizzly bears hate dogs, and that my guide dog Wickett could attract bears putting us all at risk. I wasn’t sure if he was being 100% truthful, or if his concern had more to do with me being a blind climber. I suggested he put a motion to the team and let them decide if I should go or not. Thankfully, the team voted unanimously that I could join them on the climb the next day.

The first 2/3 of the climb was spent hiking up switchbacks mainly in the forested portion of the mountain’s slope. Going up I was able to manage fine on my own by holding Wickett’s harness and occasionally letting that go and holding his leash only when the trail narrowed. The person in front of us would call out any significant hazards on the trail like fallen trees or significant rocks. It was hard going, but mainly because of the effort, not because the climb was technically difficult.

Once we cleared the tree line, we then had to traverse a significant section of scree, which mainly consists of loose rock. I was waring quality hiking boots with steel soles and toes, but Wickett just had his bare paws. I knew that if I were to cause a rock to shift, it could pinch Wickett’s paw, so I immediately decided to put Wickett on a long leash so he could walk well ahead of me. I simply held on to the six-foot leash and followed as best I could. Because we were above the treeline, and because we were ascending, even if I should trip and fall, the ground was only a matter of a few feet from my hands.

Not being able to see the other mountains around me, or the ground below, my field of remaining vision could only take in the terrain immediately around me. I started to experience mild imbalance issues because the information my limited sight was passing to my brain was saying the world had tipped. I had no long vision to counter the effect. I’ve always been good at not suffering from vertigo or seasickness, so I simply focussed on the ground at my feet and Wickett’s leash in my hands. By keeping a constant slight bit of tension in the leash, I knew there was no danger of me stepping on Wickett’s paws. I had also moved the leash contact point from the leather collar to a loop on his harness, so if necessary, he could give me a gentle pull on occasion using his shoulders and not his neck.

When we neared the summit, the going became easier since we were now walking on either hard-pack snow or bare flat rock. So far, we had been climbing up the back of the mountain, we would soon be approaching the face of the mountain from behind, which represented a straight drop of about 1,000 meters.

Once we drew near to the summit, I learned about snow cornices from our leader when Wickett drifted over with the goal of walking on the softer snow instead of the rock. The only problem was, the snow was only one meter thick, extended out past the lip of the rock, and was suspended over the edge with nothing below to hold the snow up other than wind. These cornices are created by the wind blowing snow off the back of the mountain and over the lip, where the snow would collect and build up. It was only then that Wickett was relieved of his duty to lead me, and I took the arm of one of my fellow hikers who kept us both away from the cornice, but not the summit.

Even though I had only limited peripheral vision at the time, it wasn’t that long before that I was still managing to walk around on my own with no aids what-so-ever. I can still picture the view from the top of that mountain. Looking east I could see the silver frozen lakes and green forests below and between other mountains stretching off for as far as I could see. Turning around and looking west presented a totally different view of mountain faces and their sheer rocky craggy faces stretching straight up from the ground and often disappearing into the clouds.

It started to snow, and we need to get down. While going up may have required strength, going down posed a totally new set of problems.

When we were ascending, Wickett was always slightly in front of me which meant he was a bit higher than normal and I could easily hold his harness. Going down meant Wickett was now lower than me, and the only way I could hold his harness was if I bent way over, which meant leaning forward and putting myself at risk of falling should my footing slip. It was also hard on the back.

Mainly, the problem with descending a mountain without sight is anticipating where your next step would land. Would it be somewhat lower than where you were, or would it be considerably lower causing me to lose my balance and fall. Going up wasn’t a problem because I could feel the ground with my hands if I weren’t sure about how high I needed to step. Not so going down.

Again, I had no choice but to hold the end of Wickett’s leash fully extended to six feet. The leash transmitted almost no information about the size or level of dissent Wickett was experiencing. Following behind Wickett also meant there was a chance that I could dislodge a loose rock while passing through the scree field, and that the rock could tumble down and injure Wickett’s paws or legs. I had to make sure I didn’t follow directly behind Wickett while passing through the scree field, which meant I would be walking on ground that he chose not to walk on. While Wickett chose the easiest path down, as he was trained to do, I had to follow another path that was obviously less suitable for walking.

Once we reached the tree line, one of my fellow hikers found a long stick that we could use to connect the two of us, giving Wickett a break from leading me. My fellow hiker would hold one end of the stick tucked under his arm, and I held the other end with my hand on the same side of my body that he held the stick with. The stick transmitted considerable information on the direction and the degree of dissent. It also meant that Wickett now needed to follow me through the forest, which was something he at first wasn’t comfortable doing, since it went against his training and everything we had done up until that moment. Thankfully, Wickett was had also been trained to heel, which is the command I gave him to stay by my side and a bit behind.

The snow was falling and blowing hard on our way down the mountain. Amazing just how fast the weather can change. We arrived back at our van by around 5:00 in the afternoon, after summitting a Rocky mountain that stood 3,000 meters above sea level.

I was tired for sure. Wickett seemed fine other than his paws were a bit raw from all the scrambling over rocks. We all felt great though, and I think the experience brought our team closer together.

I’m sure no one on my team or my leader had ever spent any time with someone with a visual disability. At that time, the closure of institutes for people with disabilities had just kicked into high gear, and public schools were now being attended by students with disabilities for the first time. My survival strategy throughout the public-school system, plus at that time another six years of post secondary education, was to downplay my disability. I never spoke about it to anyone, and for the most part, I looked normal. Having Wickett these past two years was the first time I ever presented myself as “blind”. It was something I wasn’t used to either. So, between the fact that my fellow field researchers and my leader had no former experience working with someone who is blind, and I had almost no experience presenting myself as blind, meant the topic pretty much never came up, or if it did, I wasn’t really able to offer up much in terms of information. Never-the-less, in true Canadian fashion, we set our differences aside and got the job done.